Differentiation as Exemplified by Consulting Work With The Dewey Schools

Despite its proven impact on student growth, differentiation remains one of the most misunderstood—and feared—practices in education. Our MV Ventures team works with schools on implementing, at scale, differentiation strategies across the K -12 spectrum. This differentiation work empowers schools and their teachers to reach all diverse learners.

As we partner with schools to implement differentiation strategies, it is clear that there are divergent definitions of what differentiation means and looks like in the classroom. What we also discovered, using survey data, is that those of us who received some form of differentiated support in our own schooling demonstrate a clearer understanding of what differentiation is versus what it is not.

“Teachers in differentiated classrooms accept and act on the premise that they must be ready to engage students in instruction through different approaches to learning, by appealing to a range of interests, and by using varied degrees of complexity and differing support systems.”1

With this in mind, there are a few recurring misconceptions about the concept of differentiation that are worth addressing:

Misconception #1: Differentiation is a strategy exclusively used to assist students who are not meeting expectations.

A misconception which leads to another common misunderstanding:

Misconception #2: Differentiation is not a strategy necessary for students meeting or exceeding expectations.

In reality, differentiation benefits all students. Differentiating does not mean giving students a greater volume of work, which is why we often reference Webb’s Depth of Knowledge framework. In this context, differentiation for students who need extension most likely means exposing them to tasks and challenges with increased levels of complexity as opposed to simply increasing the volume of work.

Increasing the complexity of tasks is an excellent way to differentiate and extend performance tasks for students who exceed expectations, but students who need intervention can also be exposed to more complex work by once again using a differentiated scaffolding strategy like backward chaining.

Misconception #3: Differentiation entails that we adjust learning outcomes, standards, and criteria for reaching proficiency for certain students who cannot meet the established targets and criteria at the pace or timing we want them to.

Differentiation is distinct from concepts like modification and personalization. This can be seen clearly by aligning differentiation with the principles of Understanding by Design (or what is more commonly called “backwards design”). Stage one of the UbD process asks us to identify the desired results, learning targets, or outcomes of a unit, performance task, or lesson, which moves us to stage two where we determine acceptable evidence for achieving stage one in the form of assessment designs and identified products or performances for showcasing student learning. Stage three is then the part of the planning process where we determine learning experiences and instructional practices that will support success in stages two and three.

Differentiation is a strategy that takes place at stages two and three in the backwards design process, but not at stage one. Different students need different learning experiences and instructional approaches as well as opportunities to show evidence of their learning in different ways in order for all students to reach the same learning targets or objectives (stage one). And this is what distinguishes differentiation from other pedagogical strategies such as modification and personalization.

Put simply, you can differentiate the content, product, or process based on interest, readiness, or a learner’s profile, but the targeted standards established in stage one of the backwards design process remain the same for all learners.

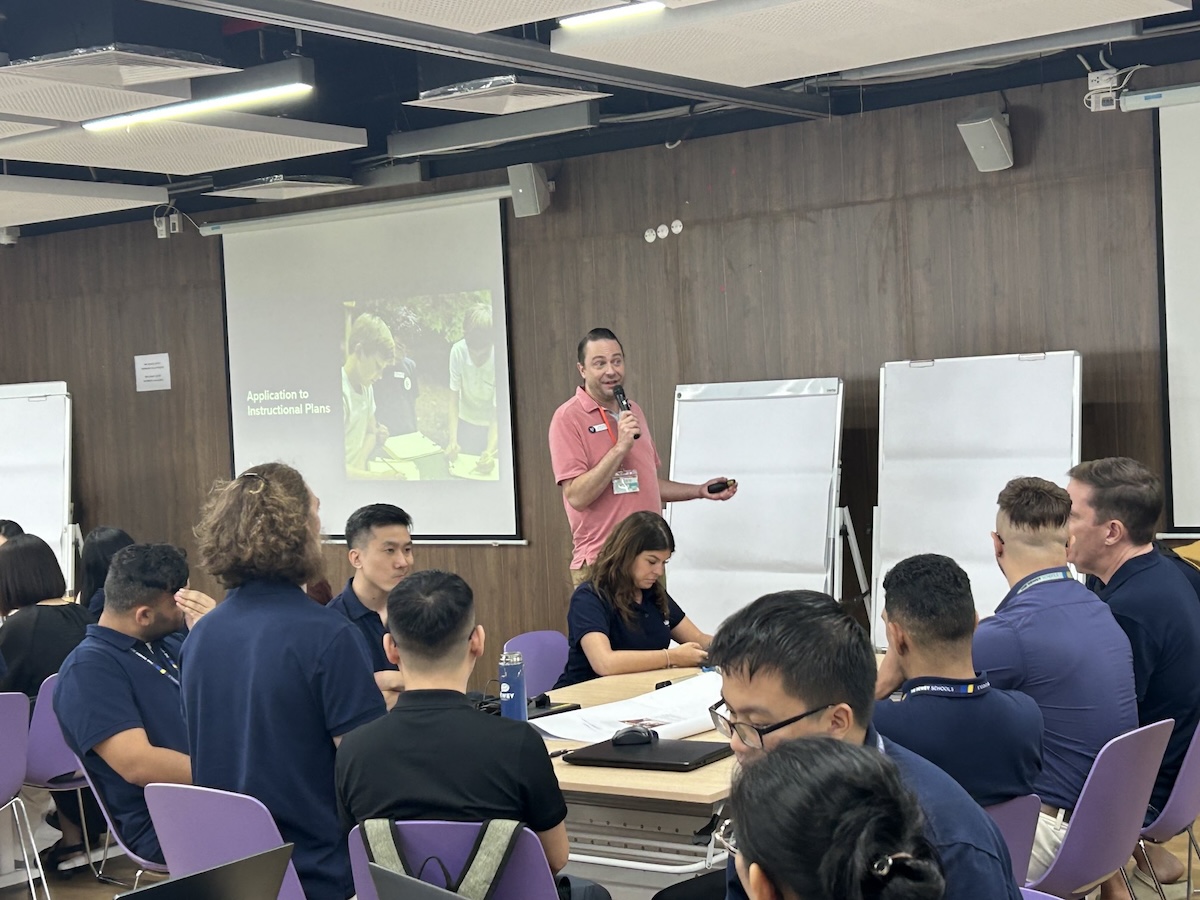

Recently our MV Ventures team led professional learning workshops on differentiation with The Dewey Schools in both Hanoi and Hai Phong, Vietnam where we worked with over 70 teachers on each campus. We introduced the faculty teams to four areas of differentiation strategies:

- Product differentiation, which gives students choice on how to show their learning.

- Flexible grouping of students, which allows us to reach and engage various student groups according to where they are at.

- Station rotation and inquiry station models, which help us create classroom procedures and workflows that serve every student, according to their needs.

- Playlists, choice boards, and tiered assessments, which give students choice for multiple entry points both for engaging content and for being assessed at a given moment in the learning cycle.

To illustrate the benefits of these strategies, we set up the experience as a set of station rotation cycles. We first set up a rotation of inquiry stations, where teachers examined and discussed examples of each strategy. In the second phase, teachers and administrators participated in a station rotation experience where at each station they were given a scenario like the following:

Ms. Johnson has just completed a pre-assessment diagnostic for her 7th-grade ELA/Humanities class. The results reveal a wide range of proficiency levels in reading comprehension. Some students are excelling with advanced vocabulary and analytical skills, while others struggle with basic sentence structure and finding the main idea. Additionally, student interest varies significantly: some love fiction and creative writing, others are more interested in non-fiction texts, current events, or graphic novels. Ms. Johnson realizes that using a one-size-fits-all approach will not meet the needs of her diverse learners. She is looking for ways to cater to both the varying skill levels and the different interests of her students.

Participants were asked:

- Which differentiation strategy would be most effective in this scenario and why?

- Let’s compound strategies to increase impact: Which of the remaining three strategies would you select and use in this scenario? Why would this second strategy be effective in this scenario as well?

The second prompt makes clear that each of these differentiation strategies are inextricably linked, and the more we integrate them together, the greater chances we have to increase impact and outcomes for learning. We ended the experience by putting participants to work, getting them to take an assignment, lesson, project, or unit and to use these strategies to create greater access for all diverse learners in their respective classes.

And much like we asked The Dewey Schools’ faculty, we pose the question to you: What do you like about these strategies? What is your ‘what if’ question after engaging in this content? And lastly, what’s next? What will you do tomorrow based on the information provided here?

We’d love to hear from you. How are you utilizing differentiation strategies to meet the needs of all the diverse learners you serve?

Need help implementing differentiation strategies at your school? MV Ventures helps schools design strategy, innovate programs and systems, and transform teaching experiences. Let’s get started on your transformation journey.

References:

1 Tomlinson, Carol Ann. The Differentiated Classroom, ASCD, 2014. P. 3-4